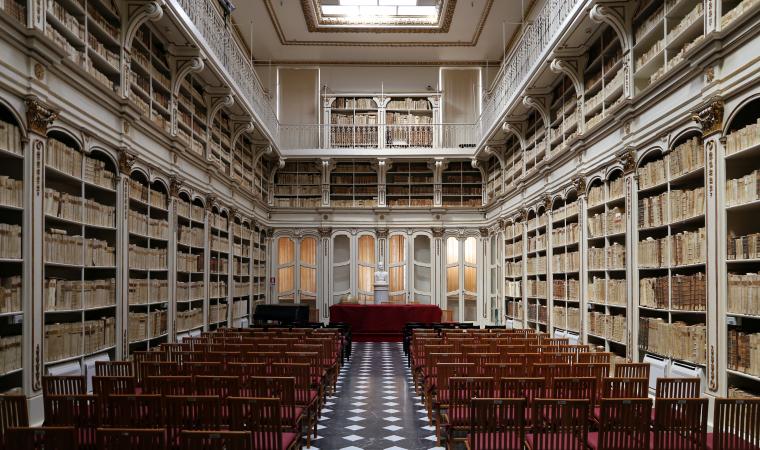

A sumptuous and ghostly art gallery outdoors. The streets of chapels and headstones in the cemetery occupy the Bonaria hill with funerary architecture and sculptures, works by the most popular artists who were active in Cagliari from half 19th century to the early 20th century. They reflect the taste of noble and high bourgeois families of the time, who rivalled against each other in their displays of wealth and power through funeral monuments.

Up until Napoleon’s decree that forbid burials in sacred places and in the centre of the city, in Cagliari the dead were buried in or near churches, with tragic consequences, including an epidemic of cholera in 1816. The cemetery was made at the foot of the hill, then in the periphery of the town, and had already been used as burial site during the Punic-Roman and paleo Christian eras.

It was built by Napoleon and consecrated in 1828. Various enlargements took it all the way to the top of the hill. It lost its function in 1968, and since then it has crystallised: no more suffering, but serenity, families without descendants, and oblivion.

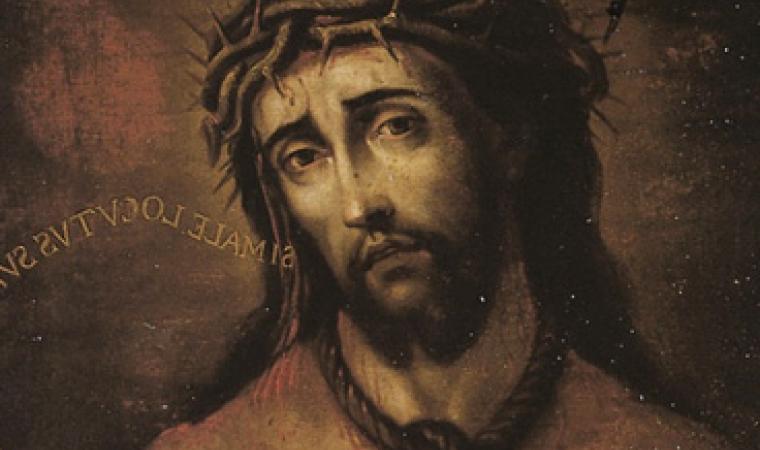

Cypresses, hibiscus, palms, pine trees and roses embrace statues and chapels, made in various and harmonised styles: baroque, Art Nouveau, neoclassic, symbolistic, ancient and military signs, as in Viale degli Eroi, for those who died in the wars. Medallions, torches, stems, obelisks, sculptures of all kinds, bas- and alt-relief decorate the tombs. Epigraphs and inscriptions complete them.

You will feel the call of the souls as you walk along the boulevards. Uphill lie the young ones: sisters holding each other in an embrace and little brothers taken away by an angel, little Efisino sitting on his epitaph, Mary leaning on a balustrade as she peeks at the visitors. Pride and tragedies: Amina, the youngest of two sisters, died at 17 (1884) as a celebrity: the first Sardinian woman to obtain a middle school diploma in a public school. At a time when only boys were encouraged to study, it was quite an accomplished, but her sister Jenny also studied, but committed suicide two years later. Higher up, ossuaries and burial recesses. Many works were signed by the so-called Michelangelo of the dead, Giuseppe Sartorio. For instance, the sculpture of attorney Todde: in the foreground is his wife, with a scarf falling over her dress, masterfully sculpted. During her 25 years as a widow, Luigia saw herself smugly in that sculpture. At the top, noble and bourgeois memories were intertwined: merchants, entrepreneurs, artists and intellectuals who put a sheen on Cagliari. Not far from the cemetery lie two basilicas worth visiting: Sardinia’s Christian temple par excellence, Nostra Signora di Bonaria, and the island’s oldest paleo Christian sanctuary, the basilica of San Saturnino, the patron saint of the city.