Operating between 1880 and 1987, the year when operations were finally discontinued, it was the most important site for the extraction and processing of antimony in Italy. During the world wars, its foundry produced 90 percent of the Italy’s total. Today, the Su Suergiu mine is a precious piece of industrial archaeology within Sardinia’s geominerary park. The name derives from the cork oaks (suergiu) that contribute to the luxuriant nature of the Sessini valley’s stream, immersed in the harsh rocky context of Gerrei, where mining villages and extraction plants reside. The stream flows under the steep-sloped and sinuous plateau, where lies Villasalto, a town that owes to its mining activity - including the minor mines of Sa Lilla and Parredis – its fame and prosperity throughout the 20th century. Deposits of antimony were discovered in the mid-19th century and led to the opening of the mine a few decades later. The metal was processed in Suergiu and then exported all over the world, used throughout the war and in pharmaceutical and cosmetics industries. The mine has always been conditioned by conflicts - the Great War completely absorbed production, the Ethiopian ‘campaign’ gave it a new impetus, the Second World War produced profits but froze its development. In the post-war period came the inexorable crisis of activity, which saw its final upsurge in the 1960s, followed by a definitive decline.

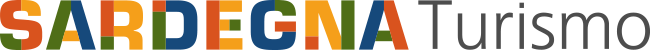

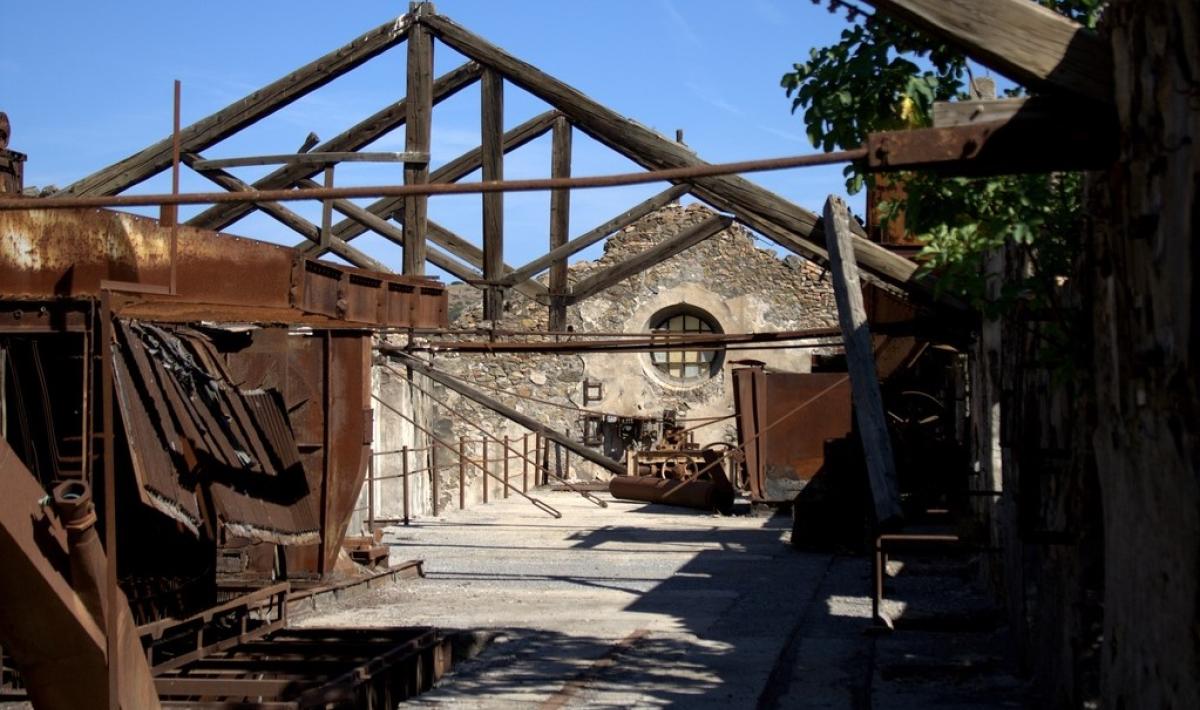

A dense wood surrounds work buildings and the village. It can be reached along an avenue lined with pine tree, leading to the 19th-century managerial building, which oversaw activities from above. Today, it houses the archaeological-mining museum, an exhibition of minerals, materials and equipment, through which the phases of the production process and the events involving the miners are reconstructed. The ‘pronaos’ entrance to the Art Nouveau-style villa features Corinthian arches and columns. The friezes are original, with leaves and festoons alternating with shovels and pickaxes. Chemical laboratory warehouses, a canteen and lodgings can be seen in the village, now having been partly converted into accommodation facilities. From the director’s office, in addition to the granite reliefs and forests of the wild area of Villasalto, the foundry can be viewed in the base of the valley, built in 1882 and formed by two structures, the oldest embellished with trusses and semi-circular lights. Works were carried out in the ‘bag chamber’ and in the ‘grill ovens’. Initially, 30 tonnes of antimony sulphide were produced per month, which was transformed into metal in Tuscany. During the war in Ethiopia, 1,700 tonnes of finished product were produced per year. Next to the foundry are the workshops for its maintenance. The set-ups overlook a piazza, with being ‘crystallised’, as if frozen in time. The long path through the woods, via which the miners reached the village, was also used by the faithful on the occasion of the feast of Santa Barbara in early June. Byzantine monks dedicated a sanctuary to the patron saint of miners, rebuilt in the mid-19th century, around which the most modern part of the town of Villasalto was constructed.